This document contains 84 Propositional Logic Exercises designed to strengthen and solidify your understanding of this fundamental area of mathematics and philosophy

These exercises complement the following theoretical reference materials:

| # | Theoretical Document | Main Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Logical Propositions | Definition of proposition, logical principles, propositional variables |

| 2 | Logical Connectives | The 6 connectives, truth tables, operator hierarchy |

| 3 | Truth Tables | Table construction, tautologies, contradictions, contingencies |

| 4 | Logical Equivalences | Equivalence laws, expression simplification |

| 5 | Rules of Inference | Modus Ponens, Modus Tollens, syllogisms, reductio ad absurdum |

| 6 | Logic Circuits | Logic gates, circuit design and simplification |

| 7 | Mathematical Proof | Proof methods: direct, contraposition, contradiction, induction |

Learning Goals

This collection provides hands-on practice in:

- Identifying propositions and determining their truth values

- Converting verbal statements into symbolic expressions

- Translating symbolic expressions back into natural language

- Evaluating compound propositions with truth tables

- Proving logical equivalences

- Applying rules of inference to arguments

- Designing and simplifying logic circuits

How This Document Is Organized

The exercises are grouped by topic, with each section beginning with a quick reference summary of the key concepts you’ll need.

Section I: Propositions and Logical Connectives

This section covers propositions and logical connectives, including how to identify propositions, symbolize statements, use connectives, and determine truth values.

Quick Reference Guide

What is a proposition?

A proposition is a declarative sentence that can be true (T) or false (F), but never both.

| Propositions ✓ | Not Propositions ✗ |

|---|---|

| “Washington D.C. is the capital of the USA” (T) | “What time is it?” (question) |

| “2 + 3 = 7” (F) | “Close the door!” (command) |

| “Water boils at 100°C” (T) | “x + 5 = 10” (contains undefined variable) |

What doesn’t count as a proposition: Questions, commands, exclamations, wishes, open sentences (containing undefined variables), and paradoxes.

Fundamental Logical Principles

| Principle | Formula | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | p ≡ p | Every proposition is identical to itself |

| Non-Contradiction | \( \mathrm{ ¬(p ∧ ¬p) } \) | A proposition cannot be T and F at the same time |

| Excluded Middle | p ∨ ¬p | Every proposition is T or F; there is no third option |

Propositional Variables

Propositional variables are lowercase letters (p, q, r, s…) that represent complete propositions.

| Variable | Proposition | Value |

|---|---|---|

| p | “5 is an even number” | F |

| q | “Brazil is in South America” | T |

| r | “Water boils at 100°C” | T |

Classification of Propositions

| Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simple (Atomic) | Contains no logical connectives | “Mary studies medicine” |

| Compound (Molecular) | Contains one or more connectives | “It rains and it’s cold” |

The 6 Logical Connectives

| Connective | Symbol | Example | When is T |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negation | ¬ | ¬p | Inverts the value of p |

| Conjunction | ∧ | p ∧ q | Only when both are T |

| Disjunction | ∨ | p ∨ q | When at least one is T |

| Conditional | → | p → q | Always, except T→F |

| Biconditional | ↔ | p ↔ q | When both have the same value |

| Exclusive Disjunction | ⊻ | p ⊻ q | When exactly one is T |

Ways to Express Connectives

| Connective | Indicator Words/Phrases |

|---|---|

| Negation (¬) | not, it is not true that, it is false that, it is not the case that |

| Conjunction (∧) | and, but, moreover, however, although, while, despite |

| Disjunction (∨) | or, either…or |

| Conditional (→) | if…then, whenever, when, only if, implies, is sufficient for, is necessary for |

| Biconditional (↔) | if and only if, when and only when, is equivalent to, is necessary and sufficient |

| Exclusive Disjunction (⊻) | either…or (but not both), exclusively |

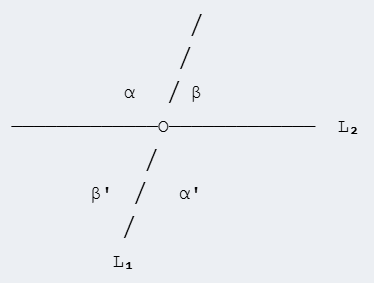

Propositions Derived from the Conditional

From a conditional p → q, the following can be formed:

| Name | Form | Example: “If it rains, then the street gets wet” |

|---|---|---|

| Direct | p → q | If it rains, then the street gets wet |

| Converse | q → p | If the street gets wet, then it rains |

| Inverse | \( \mathrm{ ¬p → ¬q } \) | If it doesn’t rain, then the street doesn’t get wet |

| Contrapositive | ¬q → ¬p | If the street doesn’t get wet, then it doesn’t rain |

Important: The direct and contrapositive always have the same truth value. The converse and inverse also have the same value as each other.

Operator Hierarchy (Order of Precedence)

| Priority | Operator | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (highest) | Parentheses | ( ) |

| 2 | Negation | ¬ |

| 3 | Conjunction | ∧ |

| 4 | Disjunction | ∨ |

| 5 | Conditional | → |

| 6 (lowest) | Biconditional | ↔ |

Example: p ∨ q ∧ r is equivalent to p ∨ (q ∧ r), because ∧ has higher precedence than ∨.

Summary Truth Tables

Negation (¬p)

| p | ¬p |

|---|---|

| T | F |

| F | T |

Conjunction (p ∧ q) → Only T when both are T

| p | q | p ∧ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | F |

Disjunction (p ∨ q) → Only F when both are F

| p | q | p ∨ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Conditional (p → q) → Only F when T→F

| p | q | p → q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | T |

Biconditional (p ↔ q) → T when both have the same value

| p | q | p ↔ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | T |

Exclusive Disjunction (p ⊻ q) → T when exactly one is T

| p | q | p ⊻ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | F |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Finding Truth Values: Step by Step

- Identify the simple propositions (p, q, r…)

- Assign truth values to each one

- Look up the result in the appropriate truth table

- Work from the inside out, respecting parentheses and operator precedence

Worked Examples

Exercise 1

Express each statement in symbolic form:

a) “If it’s cold, then it rains”

Let p: “It’s cold” and q: “It rains”

Solution

- The key words “If… then” signal a Conditional (→)

- Symbolic form: p → q

Note: Symbolic form captures the logical structure, not whether the statement is actually true.

b) “If I study, then I pass the exam, and if I pass the exam, then I go to the party”

Let p: “I study”, q: “I pass the exam” and r: “I go to the party”

Solution

- Breaking it down:

- “If I study, then I pass” → p → q

- “If I pass, then I go to the party” → q → r

- These are connected by “and” → Conjunction (∧)

- Symbolic form: (p → q) ∧ (q → r)

Note: This is the hypothetical syllogism pattern, which lets us conclude p → r.

c) “It is not true that I saw the movie and read the novel”

Let p: “I saw the movie” and q: “I read the novel”

Solution

- Breaking down the structure:

- “It is not true that…” → Negation (¬) applies to everything after

- “saw the movie and read the novel” → Conjunction (p ∧ q)

- Symbolic form: ¬(p ∧ q)

Note: By De Morgan’s Law, this is equivalent to: ¬p ∨ ¬q

d) “If you weren’t crazy, you wouldn’t have come here”

Let p: “You are crazy” and q: “You came here”

Solution

- Looking at the structure:

- “If you were not crazy” → Antecedent: ¬p

- “you would not have come here” → Consequent: ¬q

- Symbolic form: ¬p → ¬q

Note: This is the inverse of a conditional. The inverse is NOT logically equivalent to the original, but it IS equivalent to the converse (q → p).

e) “It rains and either it snows or the wind blows”

Let p: “It rains”, q: “It snows” and r: “The wind blows”

Solution

- We identify the structure:

- “It rains” → p

- “either it snows or the wind blows” → Disjunction: q ∨ r

- “It rains and (either…)” → Conjunction

- Formalization: p ∧ (q ∨ r)

Note: Parentheses matter here. Without them, operator precedence would give us (p ∧ q) ∨ r instead.

f) “Either it’s raining and snowing or the wind is blowing”

Let p: “It’s raining”, q: “It’s snowing” and r: “The wind is blowing”

Solution

- We identify the structure:

- “it’s raining and snowing” → Conjunction: p ∧ q

- “Either (the above) or the wind is blowing” → Disjunction with r

- Formalization: (p ∧ q) ∨ r

Note: Compare this with part (e): p ∧ (q ∨ r) ≠ (p ∧ q) ∨ r. Grouping changes the meaning completely.

g) “If there is true democracy, then there are no arbitrary detentions nor violations of civil rights”

Let p: “There is true democracy”, q: “There are arbitrary detentions” and r: “There are violations of civil rights”

Solution

- We identify the structure:

- “If there is true democracy” → Antecedent: p

- “no detentions nor … violations” → “neither…nor” = Conjunction of negations: ¬q ∧ ¬r

- Formalization: p → (¬q ∧ ¬r)

Note: By De Morgan, ¬q ∧ ¬r = ¬(q ∨ r). Equivalent form: p → ¬(q ∨ r)

Exercise 2

Find the truth value of each proposition:

a) If 5 + 4 = 11, then 6 + 6 = 12

Solution

- The connective is a conditional (→), signaled by “If… then”

- p: “5 + 4 = 11” → Actually 5 + 4 = 9, so p is F

- q: “6 + 6 = 12” → This is correct, so q is T

- From the truth table: F → T = T

Answer: True (T)

b) It is not true that 3 + 3 = 7 if and only if 5 + 5 = 12

Solution

- Structure: negation (¬) of a biconditional (↔)

- p: “3 + 3 = 7” → 3 + 3 = 6, so p is F

- q: “5 + 5 = 12” → 5 + 5 = 10, so q is F

- First we evaluate the biconditional: F ↔ F = T (both have the same value)

- Then we apply negation: ¬T = F

Answer: False (F)

c) Paris is in England or Tokyo is in China.

Solution

- The connective is a disjunction (∨), signaled by “or”

- p: “Paris is in England” → Paris is in France, so p is F

- q: “Tokyo is in China” → Tokyo is in Japan, so q is F

- From the truth table: F ∨ F = F (a disjunction is only false when both parts are false)

Answer: False (F)

d) It is not true that 2 + 2 = 5 or that 3 + 1 = 4

Solution

- Structure: negation (¬) of a disjunction (∨)

- p: “2 + 2 = 5” → 2 + 2 = 4, so p is F

- q: “3 + 1 = 4” → 3 + 1 = 4, so q is T

- First we evaluate the disjunction: F ∨ T = T (at least one is T)

- Then we apply negation: ¬T = F

Answer: False (F)

Exercise 3

Find the truth value of each proposition:

a) 4 + 8 = 12 and 9 – 4 = 5

Solution

- We identify the connective: conjunction (∧) by the word “and”

- p: “4 + 8 = 12” → 4 + 8 = 12, so p is T

- q: “9 – 4 = 5” → 9 – 4 = 5, so q is T

- We apply the conjunction table: T ∧ T = T (conjunction is only T when both are T)

Answer: True (T)

b) 8 + 4 = 12 and 8 – 3 = 2

Solution

- We identify the connective: conjunction (∧) by the word “and”

- p: “8 + 4 = 12” → 8 + 4 = 12, so p is T

- q: “8 – 3 = 2” → 8 – 3 = 5, so q is F

- We apply the conjunction table: T ∧ F = F (if one is F, the conjunction is F)

Answer: False (F)

c) 8 + 4 = 12 or 7 – 2 = 3

Solution

- We identify the connective: disjunction (∨) by the word “or”

- p: “8 + 4 = 12” → 8 + 4 = 12, so p is T

- q: “7 – 2 = 3” → 7 – 2 = 5, so q is F

- We apply the disjunction table: T ∨ F = T (if one is T, the disjunction is T)

Answer: True (T)

d) MIT is in California or is in Massachusetts.

Solution

- The connective is a disjunction (∨), signaled by “or”

- p: “MIT is in California” → MIT is in Massachusetts, so p is F

- q: “MIT is in Massachusetts” → Correct, so q is T

- From the truth table: F ∨ T = T

Answer: True (T)

e) Harvard is in Massachusetts or is in New York.

Solution

- The connective is a disjunction (∨), signaled by “or”

- p: “Harvard is in Massachusetts” → Correct, so p is T

- q: “Harvard is in New York” → so q is F

- From the truth table: T ∨ F = T

Answer: True (T)

f) If 5 + 2 = 7, then 3 + 6 = 9

Solution

- We identify the connective: conditional (→) by “If… then”

- p: “5 + 2 = 7” → 5 + 2 = 7, so p is T

- q: “3 + 6 = 9” → 3 + 6 = 9, so q is T

- We apply the conditional table: T → T = T

Answer: True (T)

g) If 4 + 3 = 2, then 5 + 5 = 10

Solution

- We identify the connective: conditional (→) by “If… then”

- p: “4 + 3 = 2” → 4 + 3 = 7, so p is F

- q: “5 + 5 = 10” → 5 + 5 = 10, so q is T

- We apply the conditional table: F → T = T (conditional is only F when T → F)

Answer: True (T)

h) If 4 + 5 = 9, then 3 + 1 = 2

Solution

- We identify the connective: conditional (→) by “If… then”

- p: “4 + 5 = 9” → 4 + 5 = 9, so p is T

- q: “3 + 1 = 2” → 3 + 1 = 4, so q is F

- We apply the conditional table: T → F = F (this is the only case where the conditional is F)

Answer: False (F)

i) If 7 + 3 = 4, then 11 – 7 = 9

Solution

- We identify the connective: conditional (→) by “If… then”

- p: “7 + 3 = 4” → 7 + 3 = 10, so p is F

- q: “11 – 7 = 9” → 11 – 7 = 4, so q is F

- We apply the conditional table: F → F = T (when the antecedent is F, the conditional is always T)

Answer: True (T)

Exercise 4

For the following statements:

- Pick up that pencil

- 2+5 < 6

- x-y=5

- It’s very cold

Which of the following alternatives is correct?

a) Two are propositions b) Two are open sentences c) Two are neither propositions nor open sentences d) Three are propositions

Solution

Let’s analyze each statement:

| # | Statement | Analysis | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Pick up that pencil” | It’s a command/order, has no truth value | ❌ Not a proposition |

| 2 | “2+5 < 6” | It’s a statement: 2+5=7 and 7 < 6 is F | ✅ Proposition (F) |

| 3 | “x-y=5” | Contains undefined variables | ⚠️ Open sentence |

| 4 | “It’s very cold” | It’s subjective/ambiguous, has no defined truth value | ❌ Not a proposition |

Answer: c) Two are neither propositions nor open sentences

(Statements 1 and 4 are neither propositions nor open sentences)

Exercise 5

Given the propositions: p = Mark is a merchant, q = Mark is a prosperous industrialist and r = Mark is an engineer.

Symbolize the statement: “If it is not the case that Mark is a merchant and prosperous industrialist, then he is an engineer or he is not a merchant.”

Solution

Step 1: We identify the simple propositions:

- p: “Mark is a merchant”

- q: “Mark is a prosperous industrialist”

- r: “Mark is an engineer”

Step 2: We decompose the statement into parts:

| Part of the statement | Symbolization |

|---|---|

| “It is not the case that Mark is a merchant and prosperous industrialist” | ¬(p ∧ q) |

| “He is an engineer or he is not a merchant” | r ∨ ¬p |

| “If… then…” | → |

Step 3: We join with the conditional:

\( \neg(p \land q) \rightarrow (r \lor \neg p) \)

Exercise 6

Let p: “It’s cold” and q: “It’s raining”. Write out each symbolic expression in plain English:

| # | Symbolic expression |

|---|---|

| (1) | ¬p |

| (2) | p ∧ q |

| (3) | p ∨ q |

| (4) | q ↔ p |

| (5) | p → ¬q |

| (6) | q ∨ ¬p |

| (7) | ¬p ∧ ¬q |

| (8) | p ↔ ¬q |

| (9) | ¬¬q |

| (10) | (p ∧ ¬q) → p |

Solution

Strategy: Here’s how each symbol translates to English:

| Symbol | Verbal translation |

|---|---|

| ¬ | “not”, “it is not true that”, “it is false that” |

| ∧ | “and” |

| ∨ | “or” |

| → | “if… then” |

| ↔ | “if and only if” |

(1) ¬p

- Structure: Negation of p

- Translation: “It’s not cold”

(2) p ∧ q

- Structure: Conjunction of p and q

- Translation: “It’s cold and it’s raining”

(3) p ∨ q

- Structure: Disjunction of p and q

- Translation: “It’s cold or it’s raining”

(4) q ↔ p

- Structure: Biconditional between q and p

- Translation: “It’s raining if and only if it’s cold”

(5) p → ¬q

- Structure: Conditional with negated consequent

- Translation: “If it’s cold, then it’s not raining”

(6) q ∨ ¬p

- Structure: Disjunction of q and the negation of p

- Translation: “It’s raining or it’s not cold”

(7) ¬p ∧ ¬q

- Structure: Conjunction of two negations

- Translation: “It’s not cold and it’s not raining”

Note: By De Morgan’s Law, this is equivalent to ¬(p ∨ q): “It is not true that it’s cold or it’s raining”

(8) p ↔ ¬q

- Structure: Biconditional between p and the negation of q

- Translation: “It’s cold if and only if it’s not raining”

(9) ¬¬q

- Structure: Double negation of q

- Literal translation: “It is not true that it’s not raining”

- Simplified translation (by double negation): “It’s raining”

Note: By the law of double negation, ¬¬q ≡ q

(10) (p ∧ ¬q) → p

- Structure: Conditional where the antecedent is a conjunction

- Translation: “If it’s cold and it’s not raining, then it’s cold”

Note: This proposition is a tautology (always true), since if “it’s cold” appears in the antecedent, it necessarily holds in the consequent. It’s a case of the Simplification rule: (p ∧ q) → p.

Exercise 7

Let p = “He is tall” and q = “He is handsome”. Express each statement symbolically:

| # | Verbal statement |

|---|---|

| (1) | He is tall and handsome |

| (2) | He is tall but not handsome |

| (3) | It is false that he is short or handsome |

| (4) | He is neither tall nor handsome |

| (5) | He is tall, or he is short and handsome |

| (6) | It is not true that he is short or not handsome |

Solution

Important note: “He is short” is the opposite of “He is tall”, therefore:

- “short” = ¬p (negation of p)

(1) He is tall and handsome

- Key word: “and” → Conjunction (∧)

- Symbolic form: p ∧ q

(2) He is tall but not handsome

- Key word: “but” → Conjunction (∧)

- “not handsome” = ¬q

- Symbolic form: p ∧ ¬q

Note: In logic, “but” functions identically to “and” (conjunction), even though in everyday English it suggests contrast.

(3) It is false that he is short or handsome

- Structure: Negation of a disjunction

- “short” = ¬p, “handsome” = q

- “short or handsome” = ¬p ∨ q

- “It is false that…” = Negation of everything

- Formalization: ¬(¬p ∨ q)

Note: By De Morgan, this is equivalent to: p ∧ ¬q (“He is tall and not handsome”)

(4) He is neither tall nor handsome

- Structure: “neither… nor…” = Conjunction of negations

- “not tall” = ¬p

- “not handsome” = ¬q

- Formalization: ¬p ∧ ¬q

Note: By De Morgan, this is equivalent to: ¬(p ∨ q) (“It is not true that he is tall or handsome”)

(5) He is tall, or he is short and handsome

- Structure: Disjunction where one part is a conjunction

- “tall” = p

- “short and handsome” = ¬p ∧ q

- Formalization: p ∨ (¬p ∧ q)

Note: By absorption, this simplifies to: p ∨ q

(6) It is not true that he is short or not handsome

- Structure: Negation of a disjunction

- “short” = ¬p

- “not handsome” = ¬q

- “short or not handsome” = ¬p ∨ ¬q

- Formalization: ¬(¬p ∨ ¬q)

Note: By De Morgan, this is equivalent to: p ∧ q (“He is tall and handsome”)

Answer summary:

| # | Formalization |

|---|---|

| (1) | p ∧ q |

| (2) | p ∧ ¬q |

| (3) | ¬(¬p ∨ q) |

| (4) | ¬p ∧ ¬q |

| (5) | p ∨ (¬p ∧ q) |

| (6) | ¬(¬p ∨ ¬q) |

Exercise 8

Find the truth value of each compound statement:

| # | Statement |

|---|---|

| (1) | If 3 + 2 = 7, then 4 + 4 = 8 |

| (2) | It is not true that 2 + 2 = 5 if and only if 4 + 4 = 10 |

| (3) | Paris is in England or London is in France |

| (4) | It is not true that 1 + 1 = 3 or that 2 + 1 = 3 |

| (5) | It is false that if Paris is in England, then London is in France |

Solution

(1) If 3 + 2 = 7, then 4 + 4 = 8

Step 1: Identify the component propositions:

- p: “3 + 2 = 7” → 3 + 2 = 5, so p is F

- q: “4 + 4 = 8” → 4 + 4 = 8, so q is T

Step 2: We identify the structure: Conditional (p → q)

Step 3: We evaluate using the conditional table:

- F → T = T (conditional is only F when T → F)

Answer: True (T)

(2) It is not true that 2 + 2 = 5 if and only if 4 + 4 = 10

Step 1: Identify the component propositions:

- p: “2 + 2 = 5” → 2 + 2 = 4, so p is F

- q: “4 + 4 = 10” → 4 + 4 = 8, so q is F

Step 2: We identify the structure: Negation of a biconditional ¬(p ↔ q)

Step 3: We evaluate the biconditional first:

- F ↔ F = T (biconditional is T when both have the same value)

Step 4: We apply negation:

- ¬T = F

Answer: False (F)

(3) Paris is in England or London is in France

Step 1: Identify the component propositions:

- p: “Paris is in England” → Paris is in France, so p is F

- q: “London is in France” → London is in England, so q is F

Step 2: We identify the structure: Disjunction (p ∨ q)

Step 3: We evaluate using the disjunction table:

- F ∨ F = F (disjunction is only F when both are F)

Answer: False (F)

(4) It is not true that 1 + 1 = 3 or that 2 + 1 = 3

Step 1: Identify the component propositions:

- p: “1 + 1 = 3” → 1 + 1 = 2, so p is F

- q: “2 + 1 = 3” → 2 + 1 = 3, so q is T

Step 2: We identify the structure: Negation of a disjunction ¬(p ∨ q)

Step 3: We evaluate the disjunction first:

- F ∨ T = T (at least one is T)

Step 4: We apply negation:

- ¬T = F

Answer: False (F)

(5) It is false that if Paris is in England, then London is in France

Step 1: Identify the component propositions:

- p: “Paris is in England” → p is F

- q: “London is in France” → q is F

Step 2: We identify the structure: Negation of a conditional ¬(p → q)

Step 3: We evaluate the conditional first:

- F → F = T (when the antecedent is F, the conditional is always T)

Step 4: We apply negation:

- ¬T = F

Answer: False (F)

Answer summary:

| # | Structure | Values | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | p → q | F → T | T |

| (2) | ¬(p ↔ q) | ¬(F ↔ F) = ¬T | F |

| (3) | p ∨ q | F ∨ F | F |

| (4) | ¬(p ∨ q) | ¬(F ∨ T) = ¬T | F |

| (5) | ¬(p → q) | ¬(F → F) = ¬T | F |

Exercise 9

Define a custom operator p#q that is true when p is false and q is true, and false otherwise.

Given r: “John is a doctor” and s: “John is an athlete”, find what (¬r)#s means in plain English.

Solution

Step 1: Build the truth table for the # operator

The # operator is defined as:

- p#q = T only when p = F and q = T

- p#q = F in all other cases

| p | q | p#q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | F |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Note: This custom operator returns true in exactly one case: (F, T).

Step 2: Build the truth table for (¬r)#s

We apply the definition of the # operator to the expression (¬r)#s:

| r | s | ¬r | (¬r)#s |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | T |

| T | F | F | F |

| F | T | T | F |

| F | F | T | F |

Step 3: Analyze the pattern

The column (¬r)#s has value T only when:

- ¬r = F (that is, r = T)

- s = T

This is exactly the pattern of the conjunction r ∧ s:

| r | s | r ∧ s | (¬r)#s |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F |

| F | T | F | F |

| F | F | F | F |

The columns match perfectly!

Step 4: Translate to English

Since (¬r)#s ≡ r ∧ s, the translation is:

“John is a doctor and an athlete”

Takeaway: Custom operators can sometimes be expressed using standard connectives. Here, applying # to (¬r) and s gives us the same result as the conjunction r ∧ s.

Exercise 10

For which of the following can we determine the truth value with the information given?

\( A = (p \lor q) \rightarrow (\neg p \land \neg q) \); \( V(q) = \mathrm{T} \)

\( B = (p \land q) \rightarrow (p \lor r) \); \( V(p) = \mathrm{T} \) and \( V(r) = \mathrm{F} \)

\( C = [p \land (q \rightarrow r)] \); \( V(p \rightarrow r) = \mathrm{T} \)

\( D = (p \rightarrow q) \rightarrow r \); \( V(r) = \mathrm{T} \)

Note: \( V(p) \) means the truth value of \( p \)

Solution

For each case, let’s see if we can pin down the truth value regardless of the unknowns:

In A: \( (p \lor q) \rightarrow (\neg p \land \neg q) \) with \( V(q) = \mathrm{T} \)

- We substitute q = T: \( (p \lor \mathrm{T} ) \rightarrow (\neg p \land \mathrm{F} ) \)

- \( p \lor \mathrm{T} = \mathrm{T} \) (anything OR T is T)

- \( \neg p \land \mathrm{F} = \mathrm{F} \) (anything AND F is F)

- Result: \( T \rightarrow \mathrm{F} = \mathrm{F} \)

- ✅ Sufficient (always gives F)

In B: \( (p \land q) \rightarrow (p \lor r) \) with \( V(p) = \mathrm{T} \), \( V(r) = \mathrm{F} \)

- We substitute: \( ( \mathrm{T} \land q) \rightarrow ( \mathrm{T} \lor \mathrm{F} ) \)

- \( \mathrm{T} \lor \mathrm{F} = \mathrm{T} \) (consequent always T)

- Anything → T = T (conditional with T consequent is always T)

- ✅ Sufficient (always gives T)

In C: \( p \land (q \rightarrow r) \) with \( V(p \rightarrow r) = \mathrm{T} \)

- We know that \( p \rightarrow r = T \), but this has 3 possibilities: (T,T), (F,T), (F,F)

- We cannot determine the individual values of p, q, r

- There are multiple combinations that give different results

- ❌ Not sufficient

In D: \( (p \rightarrow q) \rightarrow r \) with \( V(r) = \mathrm{T} \)

- We substitute: \( (p \rightarrow q) \rightarrow \mathrm{T} \)

- Any “thing” → T = T (conditional with T consequent is always T)

- ✅ Sufficient (always gives T)

Answer: A, B and D have sufficient information; C does not have sufficient information

Exercise 11

Given the propositions q: “4 is an odd number”, p and r any such that \( \neg[(r \lor q) \rightarrow (r \rightarrow p)] \) is true; find the truth value of the following molecular systems:

\( A = r \rightarrow (\neg p \lor \neg q) \) ; \( B = [r \leftrightarrow (p \land q)] \leftrightarrow (q \land \neg p) \) ; \( C = (r \lor \neg p) \land (q \lor p) \)

Solution

Step 1: We determine the value of q:

- q: “4 is an odd number” → 4 is even, so V(q) = F

Step 2: We analyze the main proposition:

- If \( \neg[(r \lor q) \rightarrow (r \rightarrow p)] \) is T

- Then \( (r \lor q) \rightarrow (r \rightarrow p) \) is F (by negation)

Step 3: The conditional is F only when T → F:

- \( (r \lor q) \) is T (antecedent)

- \( (r \rightarrow p) \) is F (consequent)

Step 4: If \( r \rightarrow p \) is F, then: V(r) = T and V(p) = F

Step 5: We verify: \( r \lor q = \mathrm{T} \lor \mathrm{F} = \mathrm{T} \) ✔

Summary of values: p = F, q = F, r = T

Step 6: We evaluate each schema:

| Solving | Result |

|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{A} = r → (¬p ∨ ¬q) \) \( = \mathrm{T} → (\mathrm{T} ∨ \mathrm{T}) \) \( = \mathrm{T} → \mathrm{T} = \mathrm{T} \) | A = T |

| \( \mathrm{B} = [r ↔ (p ∧ q)] ↔ (q ∧ ¬p) \) \( = [\mathrm{T} ↔ \mathrm{F}] ↔ \mathrm{F} \) \( = \mathrm{F} ↔ \mathrm{F} = \mathrm{T} \) | B = T |

| \( \mathrm{C} = (r ∨ ¬p) ∧ (q ∨ p) \) \( = (\mathrm{T} ∨ \mathrm{T}) ∧ (\mathrm{F} ∨ \mathrm{F}) \) \( = \mathrm{T} ∧ \mathrm{F} = \mathrm{F} \) | C = F |

Answer: V(A) = T, V(B) = T, V(C) = F

Exercise 12

From the falsity of the proposition: \( (p \rightarrow \neg q) \lor (\neg r \rightarrow s) \) it is deduced that the truth value of the molecular schemas:

\( A = (\neg p \land \neg q) \lor (\neg q) \) ; \( B = [(\neg r \lor q)] \leftrightarrow [(\neg q \lor r)] \) ; \( C = (p \rightarrow q) \rightarrow [(p \lor q) \land \neg q] \)

are respectively: a) TFT b) FFF c) TTT d) FFT

Solution

Step 1: We analyze the main proposition:

- If \( (p \rightarrow \neg q) \lor (\neg r \rightarrow s) \) is F

- The disjunction is only F when both parts are F

Step 2: We determine the values:

| Proposition | Condition to be F | Values obtained |

|---|---|---|

| p → ¬q = F | T → F | p = T, q = T |

| ¬r → s = F | T → F | r = F, s = F |

Summary: p = T, q = T, r = F, s = F

Step 3: We evaluate each schema:

| Solving | Result |

|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{A} = (¬p ∧ ¬q) ∨ ¬q \) \( = (\mathrm{F} ∧ \mathrm{F}) ∨ \mathrm{F} \) \( = \mathrm{F} ∨ \mathrm{F} \) | A = F |

| \( \mathrm{B} = (¬r ∨ q) ↔ (¬q ∨ r) \) \( = (\mathrm{T} ∨ \mathrm{T}) ↔ (\mathrm{F} ∨ \mathrm{F}) \) \( = \mathrm{T} ↔ \mathrm{F} \) | B = F |

| \( \mathrm{C} = (p → q) → [(p ∨ q) ∧ ¬q] \) \( = \mathrm{T} → [\mathrm{T} ∧ \mathrm{F}] \) \( = \mathrm{T} → \mathrm{F} \) | C = F |

Answer: b) FFF

Exercise 13

If the following expression is true, find the truth values of p, q and r:

\( \neg[(\neg p \lor q) \lor (r \rightarrow q)] \land [(\neg p \lor q) \rightarrow (q \land \neg p)] \)

Solution

Strategy: For a conjunction (∧) to be T, both parts must be T.

Step 1: We separate the expression into two parts

- Left part: ¬[(¬p ∨ q) ∨ (r → q)] = T

- Right part: [(¬p ∨ q) → (q ∧ ¬p)] = T

Step 2: We analyze the left part

If ¬[(¬p ∨ q) ∨ (r → q)] = T, then:

- (¬p ∨ q) ∨ (r → q) = F (by negation)

For a disjunction to be F, both parts must be F:

- ¬p ∨ q = F

- r → q = F

Step 3: From ¬p ∨ q = F

The disjunction is only F when both are F:

- ¬p = F → p = T

- q = F

Step 4: From r → q = F

The conditional is only F when T → F:

- r = T

- q = F (confirmed)

Step 5: We verify with the right part

[(¬p ∨ q) → (q ∧ ¬p)] with p = T, q = F

- ¬p ∨ q = F ∨ F = F

- q ∧ ¬p = F ∧ F = F

- F → F = T ✓

Answer:

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| p | T |

| q | F |

| r | T |

Conclusion: This type of exercise requires working “backwards” from the known truth value of the complete expression, using the properties of the connectives to deduce the values of the variables.

Exercise 14

From the falsity of (p → ¬q) ∨ (¬r → ¬s), it is deduced that the truth value of the schemas:

- A = ¬(¬q ∨ ¬s) → ¬p

- B = ¬(¬r ∧ s) ↔ (¬p → ¬q)

- C = p → ¬[q → ¬(s → r)]

are respectively:

a) FFT b) FFF c) FTF d) FTT

Solution

Step 1: We deduce the values of p, q, r, s

If (p → ¬q) ∨ (¬r → ¬s) = F, both parts must be F:

| Expression | Condition to be F | Values obtained |

|---|---|---|

| \( p → \neg q = F \) | T → F | p = T q = T |

| \( \neg r → \neg s = F \) | T → F | r = F s = T |

Summary: p = T, q = T, r = F, s = T

Step 2: We evaluate A = ¬(¬q ∨ ¬s) → ¬p

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| ¬q, ¬s | F, F |

| ¬q ∨ ¬s | F |

| ¬(¬q ∨ ¬s) | T |

| ¬p | F |

| T → F | F |

Step 3: We evaluate B = ¬(¬r ∧ s) ↔ (¬p → ¬q)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| ¬r ∧ s | T ∧ T = T |

| ¬(¬r ∧ s) | F |

| ¬p → ¬q | F → F = T |

| F ↔ T | F |

Step 4: We evaluate C = p → ¬[q → ¬(s → r)]

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| s → r | T → F = F |

| ¬(s → r) | T |

| q → T | T |

| ¬[q → ¬(s → r)] | F |

| p → F | T → F = F |

Answer:

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| F | F | F |

Correct answer: b) FFF

Exercise 15

(p ∨ q) ↔ (r ∧ s) is a true proposition, with r and s having opposite truth values. Of the following statements, which are true?

- A = [(¬p ∧ ¬q) ∨ (r ∧ s)] ∧ p, is true

- B = [¬(p ∨ q) ∧ (r ∨ s)] ∨ (¬p ∧ q), is false

- C = [(¬r ∧ ¬s) → (p ∨ r)] ∧ ¬(r ∧ s), is true

Solution

Step 1: We deduce the values of the variables

From “r and s are opposite”:

- If r = T, s = F → r ∧ s = F

- If r = F, s = T → r ∧ s = F

- In both cases: r ∧ s = F

From the biconditional (p ∨ q) ↔ (r ∧ s) = T:

- (p ∨ q) ↔ F = T

- For it to be T, both sides must be equal

- Therefore: p ∨ q = F → p = F, q = F

Summary: p = F, q = F, r ∧ s = F (with r ≠ s)

Step 2: We evaluate each statement (using r = T, s = F)

A = [(¬p ∧ ¬q) ∨ (r ∧ s)] ∧ p

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| ¬p ∧ ¬q | T ∧ T = T |

| r ∧ s | F |

| T ∨ F | T |

| T ∧ p | T ∧ F = F |

A = F. The statement says T → INCORRECT ❌

B = [¬(p ∨ q) ∧ (r ∨ s)] ∨ (¬p ∧ q)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| ¬(p ∨ q) | ¬F = T |

| r ∨ s | T |

| T ∧ T | T |

| ¬p ∧ q | T ∧ F = F |

| T ∨ F | T |

B = T. The statement says F → INCORRECT ❌

C = [(¬r ∧ ¬s) → (p ∨ r)] ∧ ¬(r ∧ s)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| ¬r ∧ ¬s | F ∧ T = F |

| p ∨ r | F ∨ T = T |

| F → T | T |

| ¬(r ∧ s) | T |

| T ∧ T | T |

C = T. The statement says T → CORRECT ✅

Answer:

| Statement | Says | Actual value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | T | F | ❌ False |

| B | F | T | ❌ False |

| C | T | T | ✅ True |

Conclusion: Two statements are false (A and B) and only one is true (C).

Exercise 16

Given the following information:

- V(r → q) = T

- V(n ∧ r) = F

- V(m ∨ n) = T

- V(p ∨ m) = F

Determine the truth value of the molecular schema:

A = [(m ∨ ¬n) → (p ∧ ¬r)] ↔ (m ∧ q)

Solution

Step 1: We deduce the values of the variables

| Condition | Analysis | Values obtained |

|---|---|---|

| \( V(p ∨ m) = \mathrm{F} \) | Disjunction F → both F | p = F, m = F |

| \( V(m ∨ n) = \mathrm{T} \) | F ∨ n = T | n = T |

| \( V(n ∧ r) = \mathrm{F} \) | T ∧ r = F | r = F |

| \( V(r → q) = \mathrm{T} \) | F → q = T | q = ?(unknown) |

Summary: p = F, m = F, n = T, r = F

Step 2: We evaluate the left side: (m ∨ ¬n) → (p ∧ ¬r)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| m ∨ ¬n | F ∨ F = F |

| p ∧ ¬r | F ∧ T = F |

| F → F | T |

Step 3: We evaluate the right side: m ∧ q

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| m ∧ q | F ∧ q = F |

Note: Regardless of the value of q, when m = F the conjunction is always F.

Step 4: We evaluate the biconditional

T ↔ F = F

Answer:

V(A) = F

Observation: This exercise demonstrates that sometimes it is not necessary to know all variables to determine the final value. The value of q remains undetermined, but it does not affect the result.

Exercise 17

If V[(q → p) → (r ∨ p)] = F, find the truth value of each of the following propositions:

- A = (p ∧ x) → (m ↔ y)

- B = (q → n) ∨ (x ∧ y)

- C = (r ↔ p) → (s ∧ q)

- D = [(s → p) ∨ (n → r)] → (x ∨ ¬x)

Solution

Step 1: We deduce the values of p, q, r

If (q → p) → (r ∨ p) = F, we need T → F:

| Expression | Condition | Values |

|---|---|---|

| r ∨ p = F | Disjunction F | r = F, p = F |

| q → p = T | q → F = T | q = F |

Summary: p = F, q = F, r = F

Step 2: We evaluate A = (p ∧ x) → (m ↔ y)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| p ∧ x | F ∧ x = F |

| F → (m ↔ y) | T |

Antecedent F → conditional always T

A = T ✓

Step 3: We evaluate B = (q → n) ∨ (x ∧ y)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| q → n | F → n = T |

| T ∨ (x ∧ y) | T |

B = T ✓

Step 4: We evaluate C = (r ↔ p) → (s ∧ q)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| r ↔ p | F ↔ F = T |

| s ∧ q | s ∧ F = F |

| T → F | F |

C = F ✗

Step 5: We evaluate D = [(s → p) ∨ (n → r)] → (x ∨ ¬x)

| Subexpression | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| x ∨ ¬x | T (tautology) |

| Anything → T | T |

x ∨ ¬x is the Law of Excluded Middle (always true)

D = T ✓

Answer:

| Proposition | Value |

|---|---|

| A | T |

| B | T |

| C | F |

| D | T |

Observation: The variables x, y, m, n, s remain undetermined, but they do not affect the final result due to the properties of the connectives.

Section II: Truth Tables

This section covers truth tables, including how to evaluate compound propositions and identify tautologies, contradictions, and contingencies.

Quick Reference Guide

What is a truth table?

A truth table shows every possible truth value of a logical expression based on all combinations of its component propositions.

Molecular Schemas and Main Connectives

A molecular schema combines propositional variables (p, q, r…) with logical connectives. We name the schema after its main connective—the one evaluated last:

| Schema | Main Connective | Name |

|---|---|---|

| p ∧ q | ∧ | Conjunction |

| p ∨ q | ∨ | Disjunction |

| p → q | → | Conditional |

| (p ∧ q) → r | → | Conditional |

| ¬(p ∨ q) | ¬ | Negation |

Components of a Truth Table

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Input columns | The first columns containing the atomic propositions (p, q, r…) |

| Helper columns | Intermediate columns for subexpressions |

| Main column | The final column showing the result of the complete expression |

Number of Rows

\( \text{Rows} = 2^n \) where n = number of distinct propositions

| Variables | Rows |

|---|---|

| 1 (p) | 2 |

| 2 (p, q) | 4 |

| 3 (p, q, r) | 8 |

| 4 (p, q, r, s) | 16 |

How to Fill Variable Columns

With n variables, each column follows a specific alternating pattern:

| Column | Pattern |

|---|---|

| 1st (leftmost) | Upper half T, lower half F |

| 2nd | Alternates in blocks of n/2 |

| Last (rightmost) | Alternates T, F, T, F… one by one |

Example with 3 variables (p, q, r):

| Row | p | q | r |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T | T | T |

| 2 | T | T | F |

| 3 | T | F | T |

| 4 | T | F | F |

| 5 | F | T | T |

| 6 | F | T | F |

| 7 | F | F | T |

| 8 | F | F | F |

Classification of Propositions

| Type | Main Column | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Tautology | All T (always true) | p ∨ ¬p |

| Contradiction | All F (always false) | p ∧ ¬p |

| Contingency | Mix of T and F | p → q |

Order of Evaluation (Operator Precedence)

| Priority | Operator | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (highest) | ( ) | Parentheses |

| 2 | ¬ | Negation |

| 3 | ∧ | Conjunction |

| 4 | ∨ | Disjunction |

| 5 | → | Conditional |

| 6 (lowest) | ↔ | Biconditional |

Truth Tables for Basic Connectives

Negation (¬p)

| p | ¬p |

|---|---|

| T | F |

| F | T |

Conjunction (p ∧ q) → Only T when both are T

| p | q | p ∧ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | F |

Disjunction (p ∨ q) → Only F when both are F

| p | q | p ∨ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Conditional (p → q) → Only F when T → F

| p | q | p → q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | T |

Biconditional (p ↔ q) → T when both have the same value

| p | q | p ↔ q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | T |

How to Build a Truth Table

- Identify all distinct propositions (p, q, r…) and the main connective

- Calculate the number of rows needed (2ⁿ)

- Set up columns for variables, subexpressions, and the final result

- Fill in variable columns with all possible T/F combinations

- Evaluate subexpressions from innermost to outermost, following precedence

- Compute the main column (main connective)

- Classify the result: Tautology, Contradiction, or Contingency

Truth Value Notation: V(p) and #V(p)

| Notation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| \( V(p) = \mathrm{T} \) | The truth value of p is True |

| \( V(p) = \mathrm{F} \) | The truth value of p is False |

| \( \# V(p) = 1 \) | Binary representation of True |

| \( \# V(p) = 0 \) | Binary representation of False |

Arithmetic formulas for connectives:

| Connective | Formula |

|---|---|

| Negation | \( \# V(\neg p) = 1 – \# V(p) \) |

| Conjunction | \( \# V(p \land q) = \# V(p) \cdot \# V(q) \) |

| Disjunction | \( \# V(p \lor q) = \# V(p) + \# V(q) – \# V(p) \cdot \# V(q) \) |

Worked Examples

Exercise 1

Build the truth table and classify:

\( \neg p \land q \)

Solution

Step 1: Count variables and determine row count

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Rows needed: 2² = 4

Step 2: Find the main connective

- Main connective: Conjunction (∧)

- Structure: (¬p) ∧ (q)

Step 3: List subexpressions to evaluate

- ¬p (negate p first)

- ¬p ∧ q (then apply conjunction)

Step 4: Build the truth table

| p | q | ¬p | ¬p ∧ q |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F |

| T | F | F | F |

| F | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | F |

Step 5: Classify the result

The main column shows both T and F values → CONTINGENCY

Takeaway: This proposition is true only when p is false AND q is true (row 3).

Exercise 2

Build the truth table and classify:

\( \neg(p \rightarrow \neg q) \)

Solution

Step 1: Count variables and determine row count

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Rows needed: 2² = 4

Step 2: Find the main connective

- Main connective: Negation (¬)

- Structure: ¬(p → ¬q)

Step 3: List subexpressions (work from inside out)

- ¬q (negate q)

- p → ¬q (apply conditional)

- ¬(p → ¬q) (negate the whole thing)

Step 4: Build the truth table

| p | q | ¬q | p → ¬q | ¬(p → ¬q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F | T |

| T | F | T | T | F |

| F | T | F | T | F |

| F | F | T | T | F |

Step 5: Classify the result

The main column shows both T and F values → CONTINGENCY

Fun fact: By the negation of conditional law: ¬(p → ¬q) ≡ p ∧ q

Exercise 3

Prove that the given proposition is a tautology:

\( [(p \lor \neg q) \land q] \rightarrow p \)

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables and calculate the number of rows

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Number of rows: 2² = 4

Step 2: Identify the main connective

- Main connective: Conditional (→)

- Antecedent: (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ q

- Consequent: p

Step 3: Identify the subexpressions to evaluate

- ¬q

- A = p ∨ ¬q, first evaluation

- (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ q (antecedent), second evaluation

- [(p ∨ ¬q) ∧ q] → p (final conditional), third and final evaluation

Step 4: Build the truth table

| p | q | ¬q | A = p ∨ ¬q | A ∧ q | [A ∧ q] → p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | T | T | T → T = T |

| T | F | T | T | F | F → T = T |

| F | T | F | F | F | F → F = T |

| F | F | T | T | F | F → F = T |

Step 5: Classification

All values in the main column are T → TAUTOLOGY ✓

Analysis: The antecedent is only T when p=T and q=T. In that case, the consequent p is also T.

Exercise 4

Prove that the proposition \( [(\neg p \lor q) \land \neg q] \rightarrow \neg p \) is a tautology.

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables and calculate the number of rows

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Number of rows: 2² = 4

Step 2: Identify the main connective

- Main connective: Conditional (→)

- Antecedent: (¬p ∨ q) ∧ ¬q

- Consequent: ¬p

Step 3: Identify the subexpressions to evaluate

- ¬p, ¬q, first evaluation (negations)

- ¬p ∨ q, second evaluation (disjunction)

- (¬p ∨ q) ∧ ¬q (antecedent), third evaluation (conjunction)

- [(¬p ∨ q) ∧ ¬q] → ¬p, final result, fourth and final evaluation (conditional)

Step 4: Build the truth table

\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|l|} \hline

p & q & \neg{p} & \neg q & [ ( \neg p \color{blue}{∨} q ) \color{green}{∧} \neg q ] \color{red}{ \rightarrow } \neg p \\ \hline

\mathrm{T} & \mathrm{T} & \mathrm{F} & \mathrm{F} & \hspace{20pt} \color{blue}{ \mathrm{T} } \hspace{13pt} \color{green}{ \mathrm{ F } } \hspace{20pt} \color{red}{ \mathrm{ T } } \\ \hline

\mathrm{T} & \mathrm{F} & \mathrm{F} & \mathrm{T} & \hspace{20pt} \color{blue}{ \mathrm{F} } \hspace{13pt} \color{green}{ \mathrm{ F } } \hspace{20pt} \color{red}{ \mathrm{ T } } \\ \hline

\mathrm{F} & \mathrm{T} & \mathrm{F} & \mathrm{F} & \hspace{20pt} \color{blue}{ \mathrm{T} } \hspace{13pt} \color{green}{ \mathrm{F } } \hspace{20pt} \color{red}{ \mathrm{ T } } \\ \hline

\mathrm{F} & \mathrm{F} & \mathrm{F} & \mathrm{T} & \hspace{20pt} \color{blue}{ \mathrm{T} } \hspace{13pt} \color{green}{ \mathrm{F } } \hspace{20pt} \color{red}{ \mathrm{ T } } \\ \hline

\end{array}

Step 5: Classification

All values in the main column are T → TAUTOLOGY ✓

Note: When the antecedent is F, the conditional is always T (vacuous truth).

Exercise 5

Build the truth table and classify:

\( (p \land q) \rightarrow (p \lor q) \)

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables and calculate the number of rows

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Number of rows: 2² = 4

Step 2: Identify the main connective

- Main connective: Conditional (→)

- Antecedent: p ∧ q

- Consequent: p ∨ q

Step 3: Build the truth table

| p | q | p ∧ q | p ∨ q | (p ∧ q) → (p ∨ q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T |

Step 4: Classification

All values in the main column are T → TAUTOLOGY

Why it works: If both p and q are true (conjunction), then at least one of them is true (disjunction). Conjunction is stricter than disjunction.

Exercise 6

Build the truth table and classify:

\( \neg(p \land q) \lor \neg(q \leftrightarrow p) \)

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables and calculate the number of rows

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Number of rows: 2² = 4

Step 2: Identify the main connective

- Main connective: Disjunction (∨)

- Structure: ¬(p ∧ q) ∨ ¬(q ↔ p)

Step 3: Identify the subexpressions to evaluate

- A = p ∧ q and its negation

- B = q ↔ p and its negation

- ¬(p ∧ q) ∨ ¬(q ↔ p) = ¬A ∨ ¬B final disjunction

Step 4: Build the truth table

| p | q | A = p ∧ q | ¬A | B = q ↔ p | ¬B | ¬A ∨ ¬B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | T | F | F |

| T | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | F | T | T | F | T |

Step 5: Classification

The main column has a mix of T and F → CONTINGENCY

Analysis: Only F when p = T and q = T.

Exercise 7

Evaluate the truth table of the compound proposition (First De Morgan’s Law):

\( \neg(p \land q) \leftrightarrow (\neg p \lor \neg q) \)

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables and calculate the number of rows

- Variables: p, q → n = 2

- Number of rows: 2² = 4

Step 2: Identify the main connective

- Main connective: Biconditional (↔)

- Left side: ¬(p ∧ q) = ¬A

- Right side: (¬p ∨ ¬q) = B

Step 3: Build the truth table

\begin{array}{|c|c|l|c|c|c|l|l|} \hline

p & q & A & \color{blue}{ \neg \mathrm{A} } & \neg p & \neg q & \color{green}{ \mathrm{B} } & \neg A \color{red}{ \leftrightarrow } B \\ \hline

T & T & T & F & F & F & F & \hspace{17pt} T \\ \hline

T & F & F & T & F & T & T & \hspace{17pt} T \\ \hline

F & T & F & T & T & F & T & \hspace{17pt} T \\ \hline

F & F & F & T & T & T & T & \hspace{17pt} T \\ \hline

\end{array}

Step 4: Classification

All values are T → TAUTOLOGY

Note: This is De Morgan’s First Law: ¬(p ∧ q) ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q

Exercise 8

Verify that the following propositions are contradictions:

a) \( (p \land q) \land \neg(p \lor q) \)

b) \( \neg[p \lor (\neg p \lor \neg q)] \)

Solution

Part a) \( (p \land q) \land \neg(p \lor q) \)

Quick analysis: This expression says “p and q are both true” AND “neither p nor q is true.” That’s clearly self-contradictory! Let’s verify with a truth table:

| p | q | p ∧ q | p ∨ q | ¬(p ∨ q) | (p ∧ q) ∧ ¬(p ∨ q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | F | T ∧ F = F |

| T | F | F | T | F | F ∧ F = F |

| F | T | F | T | F | F ∧ F = F |

| F | F | F | F | T | F ∧ T = F |

Classification: All F → CONTRADICTION ✓

Part b) \( \neg[p \lor (\neg p \lor \neg q)] \)

We could prove this algebraically, but let’s use a truth table. Setting A = ¬p ∨ ¬q, the expression becomes ¬(p ∨ A):

| p | q | ¬p | ¬q | A = ¬p ∨ ¬q | p ∨ A | ¬(p ∨ A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F | F | T | F |

| T | F | F | T | T | T | F |

| F | T | T | F | T | T | F |

| F | F | T | T | T | T | F |

Classification: All F → CONTRADICTION ✓

Why this happens: The inner expression simplifies to p ∨ ¬p (a tautology). Negating a tautology always yields a contradiction.

Exercise 9

Verify this is a contingency (3 variables):

\( [\neg p \land (q \lor r)] \longleftrightarrow [(p \lor r) \land q] \)

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables and calculate the number of rows

- Variables: p, q, r → n = 3

- Number of rows: 2³ = 8 rows

Step 2: Identify the main connective

- Main connective: Biconditional (↔)

- Left side: ¬p ∧ (q ∨ r)

- Right side: (p ∨ r) ∧ q

Step 3: Build the truth table

- Left side

| p | q | r | ¬p | q∨r | ¬p∧(q∨r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | T | F |

| T | T | F | F | T | F |

| T | F | T | F | T | F |

| T | F | F | F | F | F |

| F | T | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | T | F | F |

- Right side

| p | q | r | p∨r | (p∨r)∧q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | T | F | T | T |

| T | F | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | T | F |

| F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | F | F |

| F | F | T | T | F |

| F | F | F | F | F |

- Main connective

| ¬p∧(q∨r) | (p∨r)∧q | ¬p∧(q∨r) ↔ (p∨r)∧q |

|---|---|---|

| F | T | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | T |

| F | F | T |

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| T | F | F |

| F | F | T |

Step 4: Classification

Mix of T and F values → CONTINGENCY ✓

Note: With 3 variables, things get more complex. The outcome depends heavily on specific value combinations.

Exercise 10

Check if these two propositions are logically equivalent (3 variables):

\( [p \rightarrow (r \lor \neg q)] \) and \( [(q \rightarrow \neg p) \lor (\neg r \rightarrow \neg p)] \)

Solution

Step 1: Variables: p, q, r → 8 rows needed

Step 2: To check for equivalence, we’ll build both tables and compare their main columns.

Step 3: Build the table

Starting with p→(r∨¬q)

| p | q | r | ¬p | ¬q | ¬r | r∨¬q | p→(r∨¬q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | F | F | T | T |

| T | T | F | F | F | T | F | F |

| T | F | T | F | T | F | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | T | T | F | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | F | T | F | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | F | T | T | T | T | T |

Now with (q→¬p)∨(¬r→¬p)

| p | q | r | ¬p | ¬q | ¬r | q→¬p | ¬r→¬p | (q→¬p)∨(¬r→¬p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | F | F | F | T | T |

| T | T | F | F | F | T | F | F | F |

| T | F | T | F | T | F | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | T | T | F | T |

| F | T | T | T | F | F | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | F | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | T | T | T | T | T | T |

Step 4: Compare the main columns

| Row | p→(r∨¬q) | (q→¬p)∨(¬r→¬p) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | T | T |

| 2 | F | F |

| 3 | T | T |

| 4 | T | T |

| 5 | T | T |

| 6 | T | T |

| 7 | T | T |

| 8 | T | T |

Conclusion: The columns match exactly → Yes, these propositions are equivalent ✓

Exercise 11

Build the truth table for the following proposition (complex nesting):

\( \neg{[\neg p \lor (\neg q \rightarrow p)] \lor [(p \leftrightarrow \neg q) \rightarrow (q \land \neg p)]} \)

Solution

Step 1: Identify the variables: p, q → n = 2 → 4 rows

Step 2: This is a negation of a disjunction of two parts:

- A = ¬p ∨ (¬q → p)

- B = (p ↔ ¬q) → (q ∧ ¬p)

- Complete expression: ¬(A ∨ B)

Step 3: Evaluate step by step

Starting with schema A

| p | q | ¬p | ¬q | ¬q→p | A=¬p∨(¬q→p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F | T | T |

| T | F | F | T | T | T |

| F | T | T | F | F | T |

| F | F | T | T | F | T |

Now with B

| p | q | ¬p | ¬q | p↔¬q | q∧¬p | \( \mathrm{ B=(p↔¬q)→(q∧¬p) } \) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F | F | F | T |

| T | F | F | T | T | F | F |

| F | T | T | F | F | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | F | F |

Now we evaluate ¬(A ∨ B)

| A | B | A∨B | ¬(A∨B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F |

| T | F | T | F |

| T | T | T | F |

| T | F | T | F |

Step 4: Classification

All values are F → CONTRADICTION

Note: Even with just 2 variables, the 5 levels of nesting make this a challenging problem.

Exercise 12

We define the following operators:

| Operator | Definition |

|---|---|

| p # q | ¬p ∨ ¬q |

| p θ q | ¬(p → q) |

Evaluate the truth table of (p → q) # (p θ q) and classify it.

Solution

Step 1: First, we build the tables for the custom operators.

Table for the # operator (p # q ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q):

| p | q | ¬p | ¬q | p # q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F | F |

| T | F | F | T | T |

| F | T | T | F | T |

| F | F | T | T | T |

Note: Only F when both propositions are T.

Table for the θ operator (p θ q ≡ ¬(p → q)):

| p | q | p → q | p θ q |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | T |

| F | T | T | F |

| F | F | T | F |

Note: Only T when p is T and q is F (it’s the negation of the conditional).

Step 2: Now we evaluate (p → q) # (p θ q)

| p | q | p → q | p θ q | (p → q) # (p θ q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | ¬T ∨ ¬F = F ∨ T = T |

| T | F | F | T | ¬F ∨ ¬T = T ∨ F = T |

| F | T | T | F | ¬T ∨ ¬F = F ∨ T = T |

| F | F | T | F | ¬T ∨ ¬F = F ∨ T = T |

Step 3: Classification

All values in the main column are T → Tautology ✓

Section III: Logical Equivalences

This section covers logical equivalences, including how to simplify propositions, apply algebraic transformations, and use logical laws.

Quick Reference Guide

What is a logical equivalence?

Two propositions are logically equivalent (p ≡ q) when they share exactly the same truth values across all possible variable combinations.

We say p ≡ q if and only if p ↔ q is a tautology.

Why do equivalences matter?

- Simplify complex logical expressions

- Prove two expressions are equal without truth tables

- Transform expressions into more useful forms

- Validate logical arguments

Summary Table of the 18 Equivalence Laws

- Identity:

p ∧ T ≡ p

p ∨ F ≡ p - Domination:

p ∨ T ≡ T

p ∧ F ≡ F - Idempotence:

p ∧ p ≡ p

p ∨ p ≡ p - Double Negation:

¬(¬p) ≡ p - Complement:

p ∨ ¬p ≡ T

p ∧ ¬p ≡ F - Commutativity:

p ∧ q ≡ q ∧ p

p ∨ q ≡ q ∨ p - Associativity:

(p ∧ q) ∧ r ≡ p ∧ (q ∧ r) - Distributivity:

p ∧ (q ∨ r) ≡ (p ∧ q) ∨ (p ∧ r) - Absorption:

p ∧ (p ∨ q) ≡ p

p ∨ (p ∧ q) ≡ p - De Morgan

¬(p ∧ q) ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q

¬(p ∨ q) ≡ ¬p ∧ ¬q - Material Implication

p → q ≡ ¬p ∨ q - Contraposition

p → q ≡ ¬q → ¬p - Negation of Conditional

¬(p → q) ≡ p ∧ ¬q - Biconditional

p ↔ q ≡ (p → q) ∧ (q → p) - Biconditional (alt)

p ↔ q ≡ (p ∧ q) ∨ (¬p ∧ ¬q) - Negation of Biconditional

¬(p ↔ q) ≡ p ⊻ q - Equivalence of Negations

p ↔ q ≡ ¬p ↔ ¬q - Exportation

(p ∧ q) → r ≡ p → (q → r)

De Morgan’s Laws (essential!)

Quick tip: To negate an expression, flip ∧ to ∨ (and vice versa) and negate each part.

| Formula | In words |

|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{ ¬(p ∧ q) ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q } \) | “Not (p AND q)” equals “Not p OR Not q” |

| ¬(p ∨ q) ≡ ¬p ∧ ¬q | “Not (p OR q)” equals “Not p AND Not q” |

Extending to more propositions:

- ¬(p ∧ q ∧ r) ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q ∨ ¬r

- ¬(p ∨ q ∨ r) ≡ ¬p ∧ ¬q ∧ ¬r

Conditional Equivalences

| Law | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Material Implication | p → q ≡ ¬p ∨ q | “If p then q” = “Not p, OR q” |

| Contraposition | p → q ≡ ¬q → ¬p | The contrapositive has the same truth value |

| Negation of Conditional | ¬(p → q) ≡ p ∧ ¬q | Assert the antecedent and negate the consequent |

| Using negation | \( \mathrm{ p → q ≡ ¬(p ∧ ¬q) } \) | Alternative form |

Biconditional Equivalences

| Law | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Double Conditional | p ↔ q ≡ (p → q) ∧ (q → p) | “p if and only if q” |

| Alternative Form | \( \mathrm{ p ↔ q ≡ (p ∧ q) ∨ (¬p ∧ ¬q) } \) | True when both are T or both are F |

| Negation | ¬(p ↔ q) ≡ p ⊻ q | The negation is exclusive disjunction (XOR) |

| Equivalent Negations | p ↔ q ≡ ¬p ↔ ¬q | Negating both sides doesn’t change result |

Exportation Law

| Law | Formula |

|---|---|

| Exportation | (p ∧ q) → r ≡ p → (q → r) |

Example: “If (you study AND practice), you pass” ≡ “If you study, then (if you practice, you pass)”

How to Simplify Expressions

- Find the main connective

- Convert conditionals and biconditionals via material implication

- Apply De Morgan to push negations in or pull them out

- Use distributive, absorption, or complement laws as needed

- Reduce step by step until you reach the simplest form

- Check with a truth table if you’re unsure

Worked Examples

Exercise 1

Simplify:

\( [\neg(p \lor q) \land r] \lor [(p \lor q) \land r] \)

Solution

| Step | Expression | Law Applied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | \( [\neg(p \lor q) \land r] \lor [(p \lor q) \land r] \) | Original expression |

| 2 | \( [\neg(p \lor q) \lor (p \lor q)] \land r \) | Distributive (factor out r) |

| 3 | \( T \land r \) | Complement: A ∨ ¬A ≡ T |

| 4 | \( r \) | Identity |

Result: \( [\neg(p \lor q) \land r] \lor [(p \lor q) \land r] \equiv r \)

Takeaway: Variables p and q are irrelevant here—the expression depends only on r.

Exercise 2

Find a simpler equivalent form of the following schemas:

a) \( \neg[p \lor (p \land q)] \)

b) \( [(p \lor q) \land (q \lor r)] \land \neg q \)

c) \( \neg[\neg p \rightarrow (p \land q)] \)

Solution

Part a) \( \neg[p \lor (p \land q)] \)

| Step | Expression | Law Applied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | \( \neg[p \lor (p \land q)] \) | Original expression |

| 2 | \( \neg p \) | Absorption: p ∨ (p ∧ q) ≡ p |

Result: \( \neg[p \lor (p \land q)] \equiv \neg p \)

Why? Absorption tells us p ∨ (p ∧ q) ≡ p. Negating that gives ¬p.

Part b) \( [(p \lor q) \land (q \lor r)] \land \neg q \)

| Step | Expression | Law Applied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | \( [(p \lor q) \land (q \lor r)] \land \neg q \) | Original expression |

| 2 | \( (p \lor q) \land \neg q \land (q \lor r) \land \neg q \) | Associativity |

Simplifying (p ∨ q) ∧ ¬q:

- = (p ∧ ¬q) ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) — Distributive

- = (p ∧ ¬q) ∨ F — Complement

- = p ∧ ¬q — Identity

Simplifying (q ∨ r) ∧ ¬q:

- = (q ∧ ¬q) ∨ (r ∧ ¬q) — Distributive

- = F ∨ (r ∧ ¬q) — Complement

- = r ∧ ¬q — Identity

| Step | Expression | Law Applied |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | \( (p \land \neg q) \land (r \land \neg q) \) | Result of simplifications |

| 4 | \( p \land r \land \neg q \) | Associativity and Idempotence: ¬q ∧ ¬q ≡ ¬q |

Result: \( [(p \lor q) \land (q \lor r)] \land \neg q \equiv p \land r \land \neg q \)

Part c) \( \neg[\neg p \rightarrow (p \land q)] \)

| Step | Expression | Law Applied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | \( \neg[\neg p \rightarrow (p \land q)] \) | Original expression |

| 2 | \( \neg[p \lor (p \land q)] \) | Material Implication: ¬p → B ≡ ¬(¬p) ∨ B ≡ p ∨ B |

| 3 | \( \neg p \) | Absorption: p ∨ (p ∧ q) ≡ p |

Result: \( \neg[\neg p \rightarrow (p \land q)] \equiv \neg p \)

Exercise 3

Find the simplest schema for the proposition:

\( [(p \land q) \lor (p \land \neg q)] \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \)

Solution

Game plan: The first two terms share variable p, so we’ll:

- Factor out p using reverse distributive

- Simplify with complement

- Apply distributive for the final result

Step 1: Apply Reverse Distributive to the first two terms

Recall: (A ∧ B) ∨ (A ∧ C) ≡ A ∧ (B ∨ C)

\( [(p \land q) \lor (p \land \neg q)] \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \)

\( = [p \land (q \lor \neg q)] \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \)

Step 2: Apply Complement and Identity

Recall: q ∨ ¬q ≡ T (Law of Excluded Middle)

\( = [p \land T] \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \)

\( = p \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \) — by Identity: A ∧ T ≡ A

Step 3: Apply Distributive

Recall: A ∨ (B ∧ C) ≡ (A ∨ B) ∧ (A ∨ C)

\( = (p \lor \neg p) \land (p \lor \neg q) \)

Step 4: Apply Complement and Identity again

\( = T \land (p \lor \neg q) \) — by Complement: p ∨ ¬p ≡ T

\( = p \lor \neg q \) — by Identity: T ∧ A ≡ A

Result: \( [(p \land q) \lor (p \land \neg q)] \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \equiv p \lor \neg q \)

Takeaway: Factoring out p from the first two terms gave us q ∨ ¬q (always true), which collapsed nicely.

Exercise 4

Find an equivalent proposition to:

\( P = [(\neg p \land q) \rightarrow (r \land \neg r)] \land (\neg q) \)

Solution

Game plan: Notice the consequent is r ∧ ¬r—a contradiction (always F). We’ll:

- Eliminate the conditional via material implication

- Simplify the contradiction with complement

- Apply De Morgan and absorption to finish

Step 1: Apply Material Implication

Recall: A → B ≡ ¬A ∨ B

\( = [\neg(\neg p \land q) \lor (r \land \neg r)] \land (\neg q) \)

Step 2: Apply Complement to the contradiction

Recall: r ∧ ¬r ≡ F (Law of Contradiction)

\( = [\neg(\neg p \land q) \lor F] \land (\neg q) \)

\( = \neg(\neg p \land q) \land (\neg q) \) — by Identity: A ∨ F ≡ A

Step 3: Apply De Morgan

Recall: ¬(A ∧ B) ≡ ¬A ∨ ¬B

\( = (p \lor \neg q) \land (\neg q) \)

Step 4: Apply Absorption

Recall: (A ∨ B) ∧ A ≡ A (term A “absorbs” the disjunction)

With A = ¬q and B = p:

\( = \neg q \)

Result: \( [(\neg p \land q) \rightarrow (r \land \neg r)] \land (\neg q) \equiv \neg q \)

Key insight: When a conditional has a contradiction as its consequent, we’re saying “if the antecedent is true, something impossible happens”—which means the antecedent must be false. This is the heart of proof by contradiction.

Exercise 5

Find the simplest schema for the proposition:

\( \neg[\neg(p \land q) \rightarrow \neg q] \lor p \)

Solution

Game plan: This has the form ¬[A → B] ∨ p. We’ll:

- Apply negation of conditional: ¬(A → B) ≡ A ∧ ¬B

- Use De Morgan to handle negations

- Reduce with distributive and complement

Step 1: Apply Negation of Conditional to the main bracket

Recall: ¬(A → B) ≡ A ∧ ¬B (assert the antecedent and negate the consequent)

The antecedent is ¬(p ∧ q) and the consequent is ¬q:

\( \neg[\neg(p \land q) \rightarrow \neg q] \lor p \)

\( = [\neg(p \land q) \land \neg(\neg q)] \lor p \)

\( = [\neg(p \land q) \land q] \lor p \) — by Double Negation

Step 2: Apply De Morgan to ¬(p ∧ q)

Recall: ¬(p ∧ q) ≡ ¬p ∨ ¬q

\( = [(¬p \lor ¬q) \land q] \lor p \)

Step 3: Apply Distributive inside the bracket

Recall: (A ∨ B) ∧ C ≡ (A ∧ C) ∨ (B ∧ C)

\( = [(¬p \land q) \lor (¬q \land q)] \lor p \)

\( = [(¬p \land q) \lor F] \lor p \) — by Complement: ¬q ∧ q ≡ F

\( = (¬p \land q) \lor p \) — by Identity: A ∨ F ≡ A

Step 4: Apply Distributive again

Recall: A ∨ (B ∧ C) ≡ (A ∨ B) ∧ (A ∨ C)

\( = (p \lor ¬p) \land (p \lor q) \) — reordering by Commutativity

\( = T \land (p \lor q) \) — by Complement: p ∨ ¬p ≡ T

\( = p \lor q \) — by Identity: T ∧ A ≡ A

Result: \( \neg[\neg(p \land q) \rightarrow \neg q] \lor p \equiv p \lor q \)

Takeaway: We went from 5 connectives down to just one disjunction. Starting with negation of conditional was the key—it simplifies faster than converting with material implication first.

Exercise 6

Check if these propositions are equivalent: \( [(\neg p \lor q) \lor (\neg r \land \neg p)] \) and \( \neg q \rightarrow \neg p \)

Solution

Step 1: Variables: p, q, r → 8 rows needed

Step 2: Key observation: The second expression \( \neg q \rightarrow \neg p \) doesn’t involve r, so its value depends only on p and q.

Step 3: Let’s simplify the first expression algebraically:

- \( (\neg p \lor q) \lor (\neg r \land \neg p) \)

- By absorption: \( \neg p \lor q \lor (\neg r \land \neg p) = \neg p \lor q \) (\( \neg p \) absorbs \( \neg r \land \neg p \))

- By contraposition: \( \neg p \lor q \equiv p \rightarrow q \equiv \neg q \rightarrow \neg p \)

Step 4: We verify with a truth table:

| p | q | r | ¬p | ¬q | ¬r | ¬p∨q | ¬r∧¬p | (¬p∨q)∨(¬r∧¬p) | ¬q→¬p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| T | T | F | F | F | T | T | F | T | T |

| T | F | T | F | T | F | F | F | F | F |

| T | F | F | F | T | T | F | F | F | F |

| F | T | T | T | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | F | T | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | F | T | T | T | T | T | T | T |

Conclusion: The columns match exactly → Yes, they’re equivalent ✓

\( (\neg p \lor q) \lor (\neg r \land \neg p) \equiv \neg q \rightarrow \neg p \)

Takeaway: Variable r is irrelevant in the first expression—it simplifies right out.

Exercise 7

Simplify:

\( \{[(p \rightarrow q) \land p] \rightarrow q\} \land \{[(p \rightarrow q) \land \neg q] \rightarrow \neg p\} \)

Solution

The setup: This expression combines two classic tautologies:

- Modus Ponens: [(p → q) ∧ p] → q

- Modus Tollens: [(p → q) ∧ ¬q] → ¬p

- Step: 1

- Expression: \( {[(p \rightarrow q) \land p] \rightarrow q} \land {[(p \rightarrow q) \land \neg q] \rightarrow \neg p} \)

- Law Applied: Original expression

- Step: 2

- Expression: \( {[(\neg p \lor q) \land p] \rightarrow q} \land {[(\neg p \lor q) \land \neg q] \rightarrow \neg p} \)

- Law Applied: Material Implication: p→q ≡ ¬p∨q

Let’s simplify each part:

Left part: (¬p ∨ q) ∧ p

- = (¬p ∧ p) ∨ (q ∧ p) — Distributive

- = F ∨ (q ∧ p) — Complement

- = q ∧ p — Identity

Right part: (¬p ∨ q) ∧ ¬q

- = (¬p ∧ ¬q) ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) — Distributive

- = (¬p ∧ ¬q) ∨ F — Complement

- = ¬p ∧ ¬q — Identity

- Step: 3

- Expression: \( {[q \land p] \rightarrow q} \land {[\neg p \land \neg q] \rightarrow \neg p} \)

- Law Applied: Result of simplifications

- Step: 4

- Expression: \( {\neg(q \land p) \lor q} \land {\neg(\neg p \land \neg q) \lor \neg p} \)

- Law Applied: Material Implication

- Step: 5

- Expression: \( {(\neg q \lor \neg p) \lor q} \land {(p \lor q) \lor \neg p} \)

- Law Applied: De Morgan

- Step: 6

- Expression: \( {T \lor \neg p} \land {T \lor q} \)

- Law Applied: Complement: (¬q∨q)=T, (p∨¬p)=T

- Step: 7

- Expression: \( T \land T \)

- Law Applied: Domination: T∨A ≡ T

- Step: 8

- Expression: \( T \)

- Law Applied: Identity

Result: \( \equiv T \) (Tautology)

Why this matters: This confirms that both Modus Ponens and Modus Tollens are rock-solid inference rules.

Exercise 8

Using logical laws, simplify the following compound proposition:

\( A = [\neg(p \rightarrow q) \rightarrow \neg(q \rightarrow p)] \land [p \lor q] \)

Solution

Game plan:

- Handle ¬(p → q) and ¬(q → p) with negation of conditional

- Convert the main conditional via material implication

- Reduce using absorption and distributive

Step 1: Apply Negation of Conditional

Recall: ¬(A → B) ≡ A ∧ ¬B

| Expression | Transformation |

|---|---|

| ¬(p → q) | = p ∧ ¬q |

| ¬(q → p) | = q ∧ ¬p |

\( A = [(p \land \neg q) \rightarrow (q \land \neg p)] \land [p \lor q] \)

Step 2: Apply Material Implication to the conditional

Recall: A → B ≡ ¬A ∨ B

\( = [\neg(p \land \neg q) \lor (q \land \neg p)] \land [p \lor q] \)

Step 3: Apply De Morgan to ¬(p ∧ ¬q)

Recall: ¬(A ∧ B) ≡ ¬A ∨ ¬B

\( \neg(p \land \neg q) = \neg p \lor q \) — also applying Double Negation

\( = [(\neg p \lor q) \lor (q \land \neg p)] \land [p \lor q] \)

Step 4: Apply Absorption to the first part

Recall: A ∨ (A ∧ B) ≡ A

Reordering: (¬p ∨ q) ∨ (q ∧ ¬p) = (q ∨ ¬p) ∨ (q ∧ ¬p)

Since (q ∧ ¬p) is “absorbed” by (q ∨ ¬p), by absorption:

\( = (q \lor \neg p) \land (p \lor q) \)

Step 5: Apply Reverse Distributive

Recall: (A ∨ B) ∧ (A ∨ C) ≡ A ∨ (B ∧ C)

Reordering: (q ∨ ¬p) ∧ (q ∨ p) = q ∨ (¬p ∧ p)

\( = q \lor (\neg p \land p) \)

Step 6: Apply Complement and Identity

\( = q \lor F \) — by Complement: ¬p ∧ p ≡ F

\( = q \) — by Identity: A ∨ F ≡ A

Result: \( [\neg(p \rightarrow q) \rightarrow \neg(q \rightarrow p)] \land [p \lor q] \equiv q \)

Takeaway: A complex expression with nested conditionals collapsed to a single variable. The winning move? Hit it with negation of conditional first, then use absorption.

Exercise 9

Transform the following compound proposition to its simplest conditional equivalent:

\( P = (\neg p \leftrightarrow q) \veebar (p \rightarrow q) \)

Solution

Key insight: ¬p ↔ q ≡ p ⊕ q (negating one side of a biconditional gives you XOR)

| Step | Expression | Law applied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | \( (\neg p \leftrightarrow q) \veebar (p \rightarrow q) \) | Original expression |

| 2 | \( (p \veebar q) \veebar (\neg p \lor q) \) | Equivalence ¬p↔q ≡ p⊻q and Material Implication |

| 3 | \( [(p \veebar q) \land (p \land \neg q)] \lor [(p \leftrightarrow q) \land (\neg p \lor q)] \) | XOR Definition: A⊻B ≡ (A∧¬B)∨(¬A∧B) |

| 4 | \( (p \land \neg q) \lor (p \land q) \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \) | Absorption and simplification |

| 5 | \( p \lor (\neg p \land \neg q) \) | Inverse Distributive: p∧(¬q∨q) ≡ p |

| 6 | \( p \lor \neg q \) | Distributive and Complement |

| 7 | \( q \rightarrow p \) | Inverse Material Implication |

Result: \( (\neg p \leftrightarrow q) \veebar (p \rightarrow q) \equiv q \rightarrow p \)

Takeaway: Recognizing that ¬p ↔ q ≡ p ⊻ q was the key that unlocked everything.

Exercise 10

Simplify the compound proposition:

| \( [\neg(p \leftrightarrow q) \lor [(p \land \neg q) \lor \neg[(r \rightarrow s) \lor (q \rightarrow p)]]] \veebar [q \land (p \rightarrow q)] \) |

Solution

Game plan: Simplify each side of the XOR separately, then combine.

Step 1: Simplify the left side of XOR

We observe that ¬(p ↔ q) = p ⊻ q = (p ∧ ¬q) ∨ (¬p ∧ q)

Since (p ∧ ¬q) is already contained in p ⊻ q:

- ¬(p ↔ q) ∨ (p ∧ ¬q) = p ⊻ q — by Absorption

Step 2: Simplify ¬[(r → s) ∨ (q → p)]

| Expression | Transformation |

|---|---|

| (r → s) ∨ (q → p) | = (¬r ∨ s) ∨ (¬q ∨ p) — Material Implication |

| \( \mathrm{ ¬[(¬r ∨ s) ∨ (¬q ∨ p)] } \) | = (r ∧ ¬s) ∧ (q ∧ ¬p) — De Morgan |

This term (r ∧ ¬s ∧ q ∧ ¬p) is “absorbed” by (¬p ∧ q), which is already part of p ⊻ q.

By Absorption: (p ⊻ q) ∨ (r ∧ ¬s ∧ q ∧ ¬p) = p ⊻ q

Left side = p ⊻ q

Step 3: Simplify the right side of XOR

\( q \land (p \rightarrow q) = q \land (\neg p \lor q) \)

By Absorption: A ∧ (B ∨ A) ≡ A

\( = q \)

Right side = q

Step 4: Apply XOR property

\( (p \veebar q) \veebar q \)

Property: (A ⊻ B) ⊻ B = A (XOR is its own inverse)

\( (p \veebar q) \veebar q = p \)

| Result: \( [\neg(p \leftrightarrow q) \lor [(p \land \neg q) \lor \neg[(r \rightarrow s) \lor (q \rightarrow p)]]] \veebar [q \land (p \rightarrow q)] \equiv p \) |

Takeaway: Four variables (p, q, r, s) collapsed to just one! Variables r and s got absorbed away, and XOR-ing with q cancelled out the q from p ⊻ q.

Exercise 11

Reasoning problem:

If Diana performs activities A or B, then she performs C or D, but if she does not perform B then she performs C; however, she does not perform C. Which activities does Diana necessarily perform?

a) A b) B c) D d) B and D e) A; B and D

Solution

Step 1: We translate to propositional language

| Statement | Formalization |

|---|---|

| “If she performs A or B, then she performs C or D” | \( \mathrm{ (A ∨ B) → (C ∨ D) } \) |

| “If she does not perform B, then she performs C” | ¬B → C |

| “She does not perform C” | ¬C |

Complete expression: \( [(A \lor B) \rightarrow (C \lor D)] \land (\neg B \rightarrow C) \land \neg C \)

Step 2: We apply Material Implication to the conditionals

\( [\neg(A \lor B) \lor (C \lor D)] \land (B \lor C) \land \neg C \)

Step 3: We apply De Morgan and Absorption

- ¬(A ∨ B) = ¬A ∧ ¬B

- (B ∨ C) ∧ ¬C

=(B ∧ ¬C) ∨ (C ∧ ¬C) by Distributivity

=(B ∧ ¬C) ∨ F, by Complement

= B ∧ ¬C — by Identity

Resulting in:

\( [(\neg A \land \neg B) \lor C \lor D] \land B \land \neg C \)

Rearranging:

\( [(\neg A \land \neg B) \lor D \lor C] \land \neg C \land B \)

Step 4: We apply Distributive, Complement and Identity again with respect to ¬C:

\( [(\neg A \land \neg B) \lor D] \land \neg C \land B \)

Step 5: We apply Distributive and rearranging:

| \( (\neg A \lor D) \land ( \neg B \lor D ) \land B \land \neg C \equiv (\neg A \lor D) \land ( D \lor \neg B ) \land \neg ( \neg B) \land \neg C \) |

Step 6: We apply distributive, complement and identity with respect to \( \neg ( \neg B) \):

| \( ( \neg A \lor D ) \land D \land \neg ( \neg B ) \land \neg C \equiv ( \neg A \lor D ) \land D \land B \land \neg C \) |

Step 7: We apply Absorption to \( (¬A ∨ D) \) when we have \( D \)

- \( (¬A ∨ D) ∧ D = D \)

Then \( D \land B \land \neg C \)

Result: \( B \land D \land \neg C \)

Diana necessarily performs B and D (and does not perform C).

Answer: d) B and D

Note: This exercise shows how propositional logic can solve reasoning problems. The premise ¬C is crucial because, combined with ¬B → C (contrapositive: ¬C → B), it tells us that B is necessarily true.

Section IV: Inference Rules

This section covers inference rules, including how to check argument validity, derive conclusions, and use the shortcut method.

Quick Reference Guide

What is Logical Inference?

Logical inference is the process of drawing valid conclusions from premises using rules that guarantee sound reasoning.

An inference rule is a valid argument pattern that lets you derive a conclusion from premises. If the premises are true, the conclusion must be true.

Notation

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ⊢ | “Derives” or “entails” |

| p, q ⊢ r | From p and q, we derive r |

Equivalence vs Inference

| Concept | Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Equivalence | ≡ | Expressions have the SAME truth value |

| Inference | ⊢ | The conclusion FOLLOWS from the premises |

Conditional vs Implication

| Concept | Symbol | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|